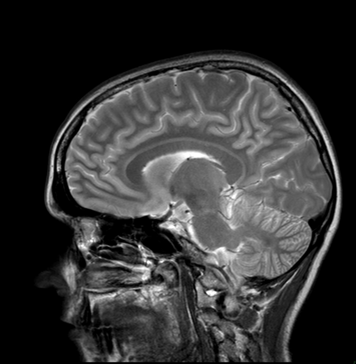

Many persons inside and outside the medical field are familiar with medical images such as the one above. MRI machines were invented to diagnose and monitor diseases and injuries that are invisible to the naked eye, but MRIs produce images that have become familiar in popular culture. Part of our visual culture, medical images, including MRIs, can influence how it is that we understand health, illness, medicine, and the body. As medical imaging technologies proliferate, they simultaneously reveal and subtly alter how it is that we should understand ourselves and how we should relate to our bodies.

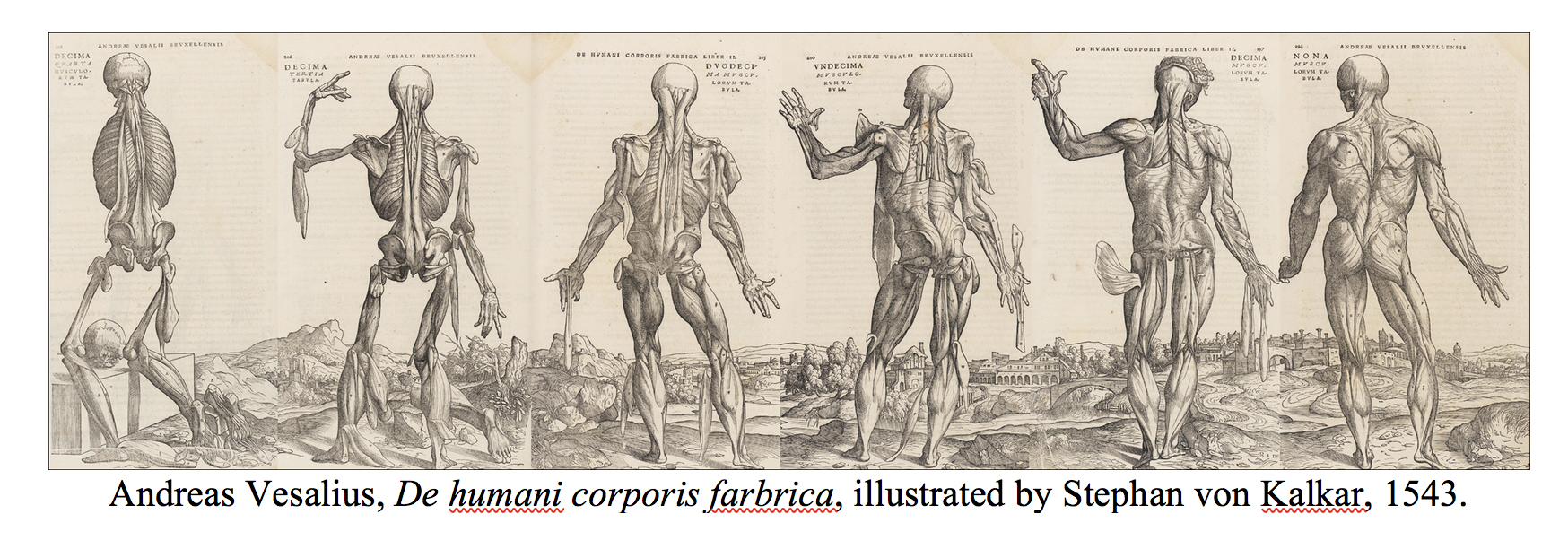

The role of medical images in our contemporary culture is hardly new. The history of medicine can be understood by its images. Before the use of photography and other more advanced medical imaging technologies, anatomists hired artists to illustrate the intricacies of human anatomy. Medical illustrations in earlier periods, however, looked far different than contemporary images in medical textbooks. From the Renaissance to the 19th century, artists were as concerned with aesthetics and theology as with as properly rendering the physical body for lay and medical education. Until the late modern era, it was a common Christian belief that one could understand something about God through understanding God’s creation. Knowing the “book of nature” helped people to know God’s “divine architecture,” of which human bodies were understood as the pinnacle. The Renaissance anatomist Andreas Vesalius and his illustrator Stephan von Calcar’s famously depicted human figures in the medical textbook De humani corporis fabrica (1543). The images, which capture flayed bodies dancing through different landscapes, are rich with metaphors of the divine, the passage of time, and mortality.

The role of medical images in our contemporary culture is hardly new. The history of medicine can be understood by its images. Before the use of photography and other more advanced medical imaging technologies, anatomists hired artists to illustrate the intricacies of human anatomy. Medical illustrations in earlier periods, however, looked far different than contemporary images in medical textbooks. From the Renaissance to the 19th century, artists were as concerned with aesthetics and theology as with as properly rendering the physical body for lay and medical education. Until the late modern era, it was a common Christian belief that one could understand something about God through understanding God’s creation. Knowing the “book of nature” helped people to know God’s “divine architecture,” of which human bodies were understood as the pinnacle. The Renaissance anatomist Andreas Vesalius and his illustrator Stephan von Calcar’s famously depicted human figures in the medical textbook De humani corporis fabrica (1543). The images, which capture flayed bodies dancing through different landscapes, are rich with metaphors of the divine, the passage of time, and mortality.

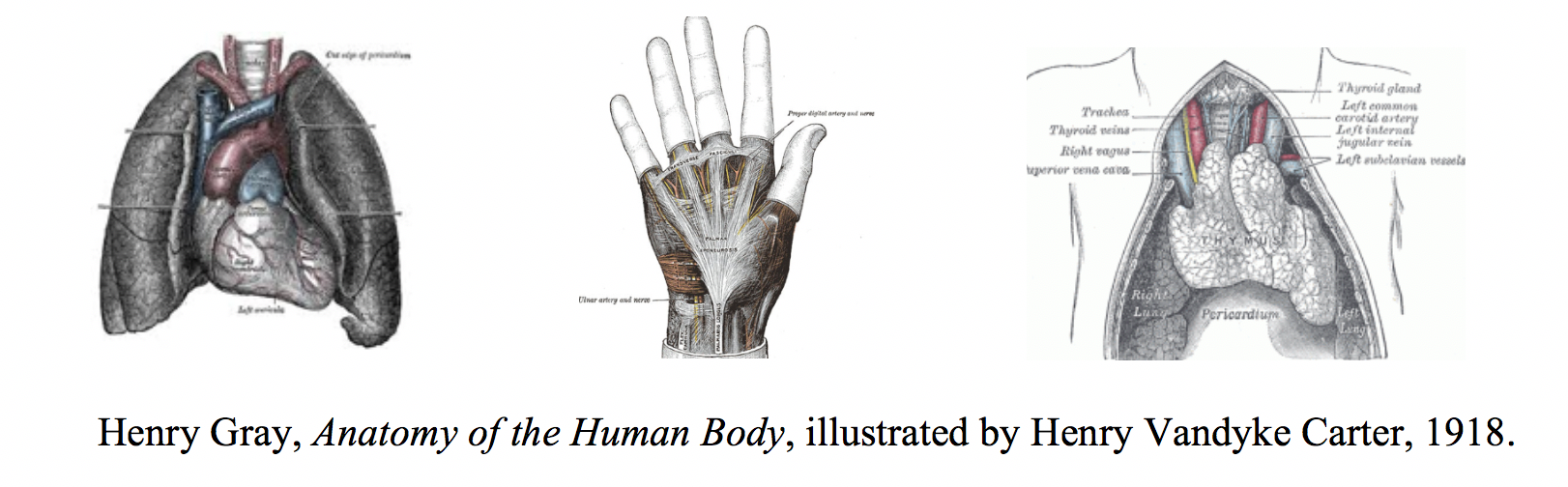

When medicine began to professionalize in the 19th century, it sought to establish itself as a legitimate branch of science and moved towards more “objective” anatomical illustrations. The unadorned style of anatomic illustration, like that in Gray’s Anatomy, soon became the norm. Attempting to avoid any particular theology, artists and anatomists looked instead to produce images that would be helpful for training new surgeons and clinicians in the latest medical techniques. The images were flat, anonymous, and in many cases detached from the rest of the body.

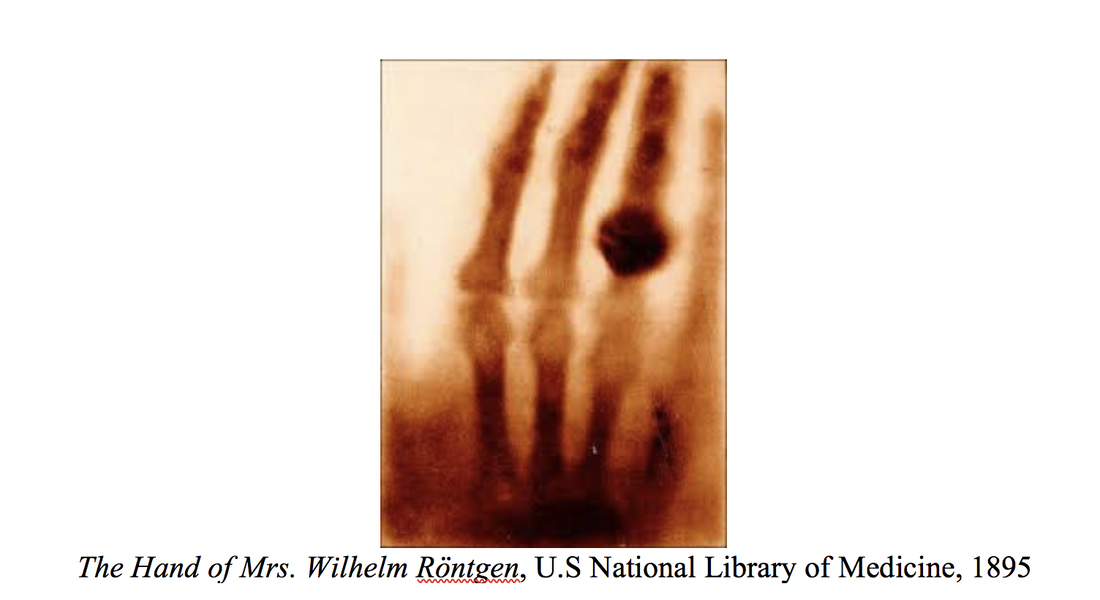

When the X-ray was introduced in 1895, it was not initially seen as superior to, or more objective than, other medical images. X-rays allowed for a new, more intimate look into the human body and were not confined to the medical realm. Wilhelm Röntgen, who discovered X-rays, captured a now famous radiograph of his wife Anna’s hand, including her wedding ring (Anna noted that the image disturbed her, reminding her of her death).

X-rays became a sensation in popular culture, allowing women to see their unborn children and shoe shoppers see the bones in their feet before scientists realized how dangerous x-rays could be. Attempts were then made to keep medical imaging technologies confined within the health care system, where they could be used safely and interpreted appropriately. With the advent of CAT scan, MRI, and other more sophisticated medical technologies, medical images became more difficult to interpret without a medical degree and, therefore, less accessible by non-clinicians.

Over the past three decades, digital imaging has helped to transform medicine, but it has not necessarily helped patients to better understand their own bodies. Images such as MRIs are thought to help mediate the physician’s diagnosis and the invisibility of certain diseases, but it is unclear how helpful MRIs are with this quest. Medical images provide objective data to clinicians, but they are far removed from how patients experience illness or see themselves. Medical images no longer point the viewer toward God, the human experience, or the context in which bodies are situated. Instead, the bodies presented in contemporary diagnostic imaging are fragmented, colorless, fleshless, silent, still, and transparent. Human bodies are made into objects in the scanning process, so that data can be abstracted from them. As a result, physicians are sometimes tempted to look to these images to make sense of illness, rather than the living, breathing person in front of them.

I was diagnosed with a chronic illness with the aid of MR images. It took my neurologist all of 30 seconds looking at my MRIs to know that I had multiple sclerosis. At that time, nothing about this image of me felt familiar. It could have been anyone’s head, anyone’s brain. It did not look like me, nor did it look diseased to me. The physician, however, trained to interpret MRIs, immediately saw the bright white spots that shouldn’t be there, which signaled missing nerve connections. For this physician, like so many physicians trained to see human bodies first as broken apart images in a textbook, then as corpses, and only lastly as living persons, the MRI became the primary way he saw me. He had a hard time looking me in the eye, but he was very comfortable interpreting my MRIs. I was not satisfied, however, to let this image of my ill-body be the one that defined me. Knowing a bit about the history of medical imaging, I sought other ways to visualize my experience of illness.

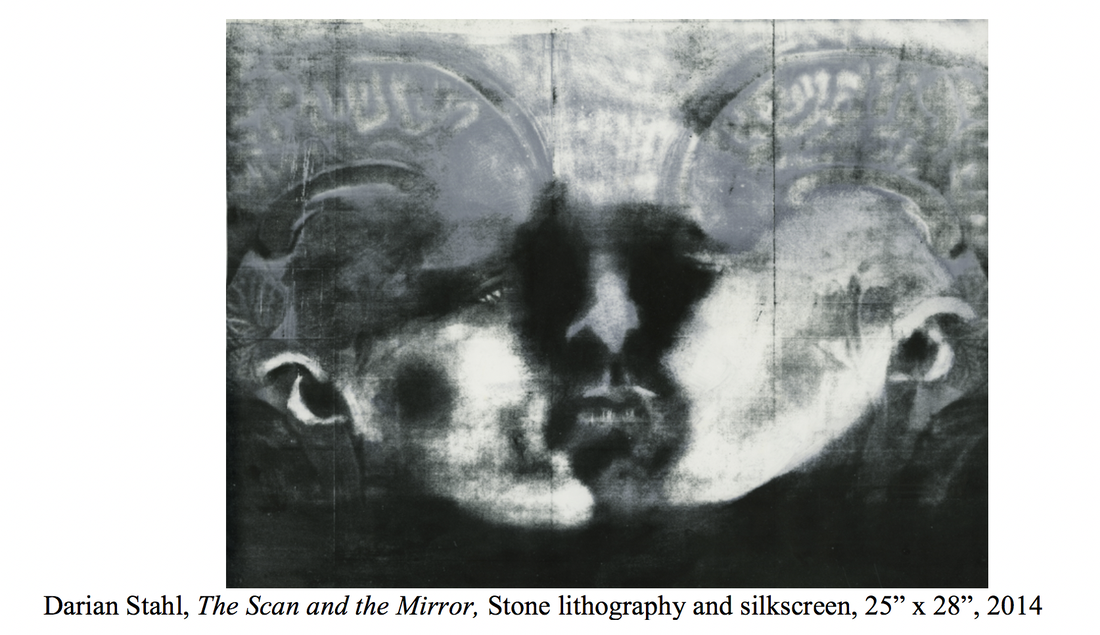

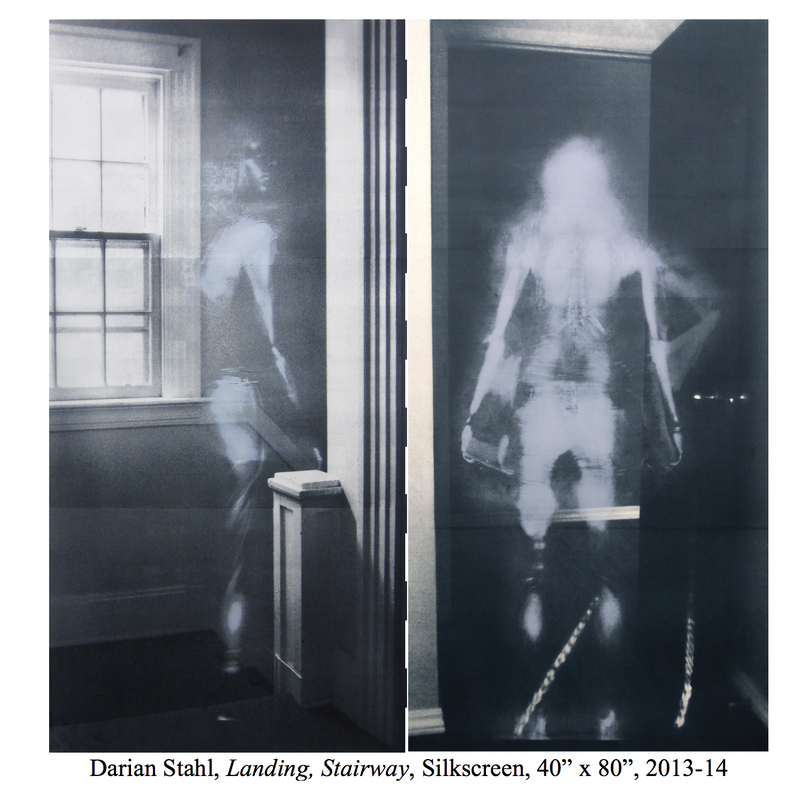

I was fortunate to have an artist in my family, my sister Darian Goldin Stahl. In discussing my illness with Darian, we realized that the history of anatomical illustration allowed for a different way of seeing the body. Darian began incorporating my MRIs into her printmaking. Attempting to give flesh back to the images, Darian invented a way of “scanning” her skin onto the MRIs by creating an impression of her body in charcoal. The joining of scan and skin creates a new figure, which incorporates the MRI, but puts the body in context and gestures toward the unfolding and becoming of the body in illness.

Over the past three decades, digital imaging has helped to transform medicine, but it has not necessarily helped patients to better understand their own bodies. Images such as MRIs are thought to help mediate the physician’s diagnosis and the invisibility of certain diseases, but it is unclear how helpful MRIs are with this quest. Medical images provide objective data to clinicians, but they are far removed from how patients experience illness or see themselves. Medical images no longer point the viewer toward God, the human experience, or the context in which bodies are situated. Instead, the bodies presented in contemporary diagnostic imaging are fragmented, colorless, fleshless, silent, still, and transparent. Human bodies are made into objects in the scanning process, so that data can be abstracted from them. As a result, physicians are sometimes tempted to look to these images to make sense of illness, rather than the living, breathing person in front of them.

I was diagnosed with a chronic illness with the aid of MR images. It took my neurologist all of 30 seconds looking at my MRIs to know that I had multiple sclerosis. At that time, nothing about this image of me felt familiar. It could have been anyone’s head, anyone’s brain. It did not look like me, nor did it look diseased to me. The physician, however, trained to interpret MRIs, immediately saw the bright white spots that shouldn’t be there, which signaled missing nerve connections. For this physician, like so many physicians trained to see human bodies first as broken apart images in a textbook, then as corpses, and only lastly as living persons, the MRI became the primary way he saw me. He had a hard time looking me in the eye, but he was very comfortable interpreting my MRIs. I was not satisfied, however, to let this image of my ill-body be the one that defined me. Knowing a bit about the history of medical imaging, I sought other ways to visualize my experience of illness.

I was fortunate to have an artist in my family, my sister Darian Goldin Stahl. In discussing my illness with Darian, we realized that the history of anatomical illustration allowed for a different way of seeing the body. Darian began incorporating my MRIs into her printmaking. Attempting to give flesh back to the images, Darian invented a way of “scanning” her skin onto the MRIs by creating an impression of her body in charcoal. The joining of scan and skin creates a new figure, which incorporates the MRI, but puts the body in context and gestures toward the unfolding and becoming of the body in illness.

Feeling the need to give flesh back to my body, Darian donated her own flesh to my MRI in the image above. She began with my face, the part of my body that most clearly represents me and the part our bodies that most resemble one another. The image presents a trinitarian relationship. The merging of our bodies creates not just one but two faces, gazing toward one another, intimately confronting one another. As they do, a third visage emerges in between, which witnesses to our communal bond and the new creation that is born from our collaborative effort. In this artwork, the body cannot be contained to a single image, it is excessive and multiple—one face becomes two become three. The multiplicity of this figure invites viewers to see themselves as part of the communal body.

Our collaborative project would not have been possible if I had not been willing to be vulnerable with Darian by sharing my images and experience of illness. I now view my vulnerability as a gift that Darian faithfully receives and transforms [2]. In Darian’s art, my medical images become icons—doorways that reveals the truth of the body, which, as a Christian, I believe was created in the image and likeness of God’s own body. Recalling and older tradition in anatomical illustration, Darian’s art suggests to the viewer that the body is created and given meaning by God. This is the body that Christ inhabited and the Spirit dwells within—the ill, vulnerable body. God’s immanence shines forth in the image—the God who chooses to dwell with us, chose to become vulnerable to save us, and chooses to be for us, not in spite of our infirmities, but along with them. This, not power, strength, and superior rationality, is what it means to be human. Darian’s art challenges viewers to reconsider what the ideal body really is and what the body is for.

[1] Dariangoldinstahl.com

[2] D. Stahl, Imaging and Imagining Illness: Becoming Whole in a Broken Body. Eugene, OR: Cascade Books. 2018.

[1] Dariangoldinstahl.com

[2] D. Stahl, Imaging and Imagining Illness: Becoming Whole in a Broken Body. Eugene, OR: Cascade Books. 2018.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed